When I read Jez Humble’s book Continuous Delivery a few years ago, I felt like I was being watched. I thought Jez had been monitoring us and watching us struggle with deployments. In 2015, Maxwell Health released once a week. It was a coordinated affair and rife with what we discovered were anti-patterns. We would deploy off-hours, we coordinated deployments between teams, and each environment had its own build. If things went wrong, we would try to fix forward. It caused unnecessary stress, introduced risk for our customer experience and our software, and we had to make a change.

Today, Maxwell deploys code to production dozens of times a day without incident. It took coordination and dedication to change our process, and it was well worth the effort.

We ship small artifacts

In our old deployment pipeline, we tied our branching strategy to our deployments. Our strategy was a variation on git flow. When creating a new feature, an engineer would branch off of master and name your branch feature-abc. We then had a branch for each of our environments - QA, Staging, and Production. The engineer merged their branch to the QA branch for testing. Once the feature passed testing, the _feature-abc _branch could then be merged a second time, this time to master, and master would be merged into the staging and production branches. Each merge was its own build and this process encouraged mismatches between environments. What was on QA wasn’t guaranteed to be exactly what was deployed to staging or production.

After experiencing confusion, coordination issues, and too many mis-merged features, we adopted a version of Github Flow. An engineer creates a branch off of master as they had before. Once approved, the engineer testing that code merges the branch to master. The build pipeline then builds an artifact, in our case a docker image, and deploys it to our QA environment. Each commit once on master needs to be deployable. This keeps the pipeline clear and able to be deployed to production without incident. Each commit being deployable also means that authors must have strong automated tests to ensure confidence in their change. If it fails any testing on the QA environment or blocks the pipeline for whatever reason, we revert it.

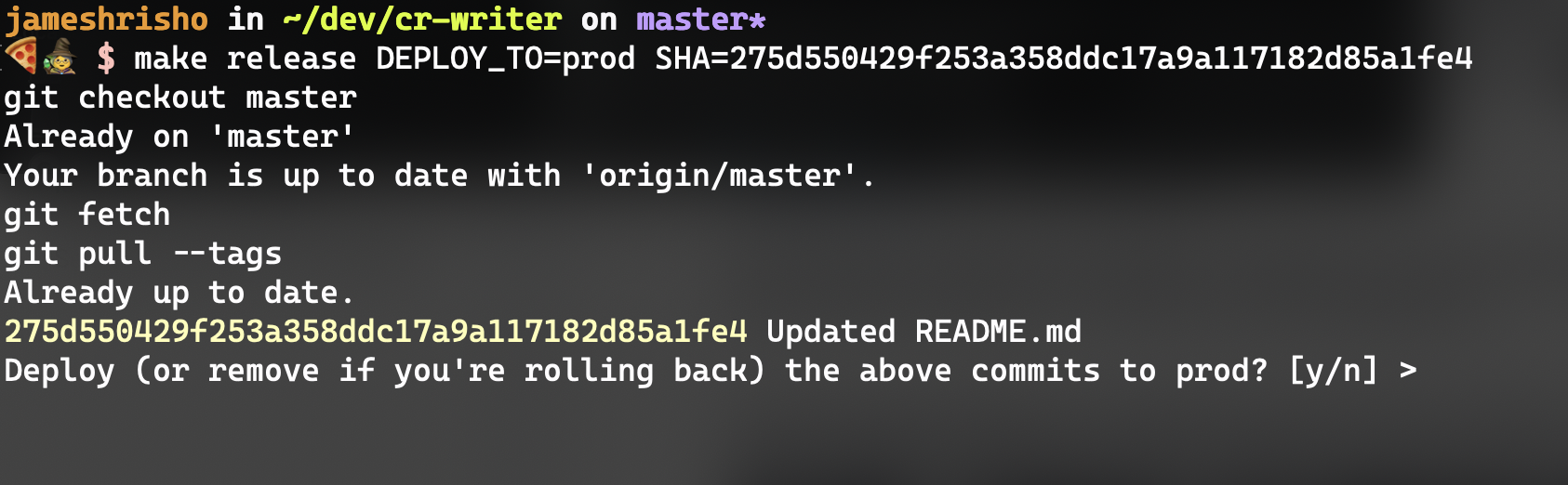

If exploratory testing is successful in QA, the team can then ship that artifact to other environments by creating a Git tag. Our build tool knows, based on the name of the tag, to ship the artifact from that Git hash to the target environment. We even simplified it by building a small make command for it.

Our tooling also enables quick rollback. To rollback, you would call the same command for a SHA you want to go back to. Usually the previous deployment.

Our old branching strategy encouraged long-lived branches. There would be painful merge conflicts, different merge order on QA vs production, and each environment would behave slightly different. To accommodate the Github flow/artifact approach, each change needed to be small, releasable, and well tested. With smaller releases, both improvements and bug fixes are easier to reason about and verify. Our code review process is less painful, and we have fewer incidents in production.

SLOs for Builds, Deployments, and Rollbacks

We decided it is important to focus on rollbacks as part of our strategy. In the past, we would fix forward instead of rollback. Fixing forward, while well-intentioned, encouraged us to make matters worse. We would try to make changes while under duress. In the worst cases, we caused bugs in production while trying to fix other issues.

Instead, we want rollbacks to be the first tool in our engineers’ toolboxes. Our guideline is for our teams to make rollbacks possible less than a minute. As a result, the quickness of a rollback makes it the default instead of the last resort. Since our rollback strategy is identical to deployment (using a make command to send a specific Docker image to a specific environment), our deployment time also improved.

We also encourage builds to be less than 10 minutes. Our branching strategy encourages reverts and merging to master more often. Each of these events trigger builds, so long builds are an interrupt for teams. We must keep build times as short as possible. We spend money both on our team’s time and our build server’s time while we build. So time spent building should be minimal.

Identical Environments

To enable confidence in our deployments, we had to be certain of our environments. If one environment is quite different, we open ourselves up for bugs. The right way to do this is to invest in the tools that make your infrastructure repeatable and auditable. For us, that meant investing in our infrastructure-as-code strategy. At Maxwell, we leverage Docker, Terraform, Kubernetes, and other tools to make sure that our environments are as similar as possible.

Separating Release From Deployment

Finally, Maxwell encourages our teams to separate the concepts of deployment and release. We even made sure our vocabulary on the topic was well defined. Deployments are the act of moving code to an environment, while releases are the process of making functionality available to a stakeholder. Although we deploy several times a day, our releases might be less frequent, and are controlled by our product owners. Releases usually consist of more than one small change. Releases might include coordination of several teams work. For example, one team might be building the reporting functionality that is tied to new data we’re collecting. We would want to release that to our customers together but not have to coordinate the deployment of their code. Releases also include training for internal stakeholders, or a communication to our customers.

We enable this separation of releases and deployments by the use of feature toggles. Feature toggles allow us to hide functionality to all or a portion of users. We use an open-source library but there are many options for how to manage toggling your code. Our deployments have become much safer as putting work behind a feature toggle means we can deploy incremental parts of a feature rather than waiting for the entire feature to be complete and pushing a large body of code to production at once. Toggles also ensure that our functionality works in production without disrupting our customers. When our product team feels a feature is ready they can then turn on a feature toggle when they are ready.

Metrics For Success

These are a small number of the many changes our organization has made to become more efficient. We’re constantly improving our processes, including in how we monitor, alert, and test. We are quick to respond to our customers. But more importantly, we’re more confident in our work each day.

We started with metrics that we felt would make our teams successful. We knew we wanted to optimize for more frequent deployments and fewer incidents related to them. We wanted to minimize the number of times we fixed forward, as we recognized that as a failed release. We wanted the frequency that we ship code to be separated from the frequency we released to customers. Before starting the journey to continuous delivery, consider the objectives you are trying to achieve. In order to determine success, create metrics that measure a team’s progress over time. These goals should have a reasonable end state in mind. For example, a build can always be faster, but what length of time is a success for your team? Chances are, the answer will be unique to the tools you use and the domain of your business.

While the journey can be challenging, don’t give up. Each improvement builds upon itself. We’ve found that every six months we’re unrecognizable to the organization we were six months before that. We’re a more mature, yet more nimble version of ourselves.